An Ode to Marcia

“I don’t believe an accident of birth makes people sisters or brothers. It makes them siblings, gives them mutuality of parentage. Sisterhood and brotherhood is a condition people have to work at.”

— Maya Angelou

The first time I saw this quote from Dr. Angelou, it gave me goosebumps. Never before had I felt so seen, so validated. I had been proclaiming something similar to close confidants for some years now. “For me, the word ‘sister’ is a verb,” I’d say. “To be a sister is an action. To be ‘sisterly’ is an adverb, you know?” It is a title I have always taken intensely serious. With so many landmines to navigate in this life, there is enough strife to go around. To be a sister is, among many things, to embody a soft place to land. Sisterhood is a sacred space, a supernatural destination. A space to hold secrets. To experience a unique and irreplaceable love. There is nothing light about being a sister. It is for the fiercely committed.

The thing about sisterhood is that it means different things to different people. And sometimes the variance of interpretation can determine the fate of the relationship. When the sentiments of sisterhood align, there is nothing quite as euphoric. And maybe they won’t align the whole time. Maybe only for a season. Maybe for many seasons throughout your lifetime, or between droughts. Somehow, thankfully, I have always understood that the synchronistic occurrences over the course of sisterhood are like gold, and the heart acts as a storehouse for the bottled treasures we call memories.

Today is my sister’s birthday. It is also 4 months to the day since my birthday. It also marks 4 months and 3 days since her transition from this earthly plane — 123 days since she became an ancestor. It is a reality that, for me, grows more and more peculiar, surreal, gut-wrenching, mystical, humbling, mind-boggling, and divine with every passing day. In many ways, it’s my worst fear come to life. When you’re the youngest of many older siblings, you think about these things. At least I did. Almost incessantly, as a child. In fact, this somewhat irrational fear lived in the back of my mind for many years. When you experience the sanctity of sisterhood — for no matter how long — you want it forever. You want it to stay at its best forever. You want it to survive the cold winters, and the dark nights. You want it to last long enough to tend to the frostbitten parts that still feel tender. You want the sun’s warmth to act as a salve. You want to experience the tiny green sprouting buds that offer hope. You want to dance under the glorious full blooms.

I never lived with my sister. By the time I was born, she — like many of my grandparents’ “grands” — found escape and solace in their Brooklyn dwelling. But I was still uptown residing in our Bronx birthplace. By the time I was about 4 years old, the physical distance had stretched three thousand miles across the country. She’d moved to Los Angeles, planting new roots, and tending to her abundant harvests over the next several decades. Though exactly 15 years and 8 months and a lifetime of contrasting experiences were between us — my sister Marcia and me — oftentimes and in many ways we could find ourselves closer than anyone at any given moment. It was in these moments that the distance felt completely inconsequential. When we were finishing each other’s sentences, sharing a mischievous laugh, being the other’s amen corner when expressing our individual principles, or vibing on a song, she could have been on the other side of the world and it would have mattered not.

She graduated high school early, and her academic astuteness earned her a scholarship to College of the Holy Cross, an elite liberal arts institution that is one of a select few to academically rival the Ivy League. She forewent her scholarship, deciding instead to venture west and alchemize her future, her way. This profoundly impacted me, her decision functioning as a guidepost for me when I decided that my combination of full-time college, a full-time internship, and late-night moonlighting was going to give me a nervous breakdown if I didn’t let one of those pressures go. By this time, my sister had been thriving professionally for well over a decade. She made taking the road less traveled feel totally doable and even enchanting.

She worked in advertisement and was consistently the company’s top gun. She’d take me to work with her when I would make my annual visits to LA, and there her name would be, looming like a Broadway marquee at the highest spot on the dry eraser board in all caps. You had to look all the way up to see it. You had to tilt your neck back to take in her greatness. To see Marcia, to get the essence of her intentions in this life, you had to extend your purview. Her path and her triumphs demanded it.

I was always looking up to Marcia, even when I grew taller in height by the time I turned 15, playfully teasing her about the inch and a half I had on her. She was a vision to behold. She had these large, penetrating eyes that seemed to look through to your entire soul. Her skin was smooth and buttery. To this day, she is the only person I know who had a deep widow’s peak in the middle of her forehead. It led to this glorious mane of jet black, silky hair that fell to the middle of her back. She was statuesque and walked with an exaggerated, but completely natural switch of her hips. Watching her walk away with that confident and seductive gait as her hair ricocheted from one side to the other was something to behold. Her scent was bewitching and signature. It was always irresistible. I’d smelled perfume on women before, but never like her. It was always so present, but somehow also mysterious and understated. It was so hypnotizing that as a teenager I started wearing it too, hoping to capture the allure that she had. It smelled great on me. On her, it subsumed into her aura.

She wore a blue-based red matte lipstick most of the time. I know that because when I started wearing makeup, she taught me that this color was perfect against skin with undertones “like ours.”

“You don’t want to wear anything that looks too-too orangey… unless it’s [MAC’s] Russian Red,” she strongly advised. “You want something with a blue base.” I was always at attention when she offered beauty tips. I didn’t want to miss a single word. Her tips felt sacred. She had naturally defined, full lips that required no liner and her brows had a deep natural arch that women pay through the nose to obtain. She was a natural beauty in every sense of the word. Feature for feature, we didn’t really look alike. Her jet, straight hair was nothing like my kinky, bushy, brown coils. Her deep ebony eyes contrasted my probing hazel-amber ones. We tried several times, but we could never quite share each other’s foundation – her butter pecan just a few hues too many away from my caramel sundae. Yet somehow, when you put it all together, we were undoubtably sisters, and I reveled in anyone’s observation of it. I wanted to be just like her. She was everything to this little girl.

As a result of her move across country, when I was a child I saw her only on occasion, making her visits to New York more like national holidays. The anticipation of her arrival would be felt for weeks. The time between her landing on the runway of JFK and the time she would arrive at my house felt unbearable. When she finally showed up, I was overwhelmed by a joy and bliss that I can still tap into at this moment. There isn’t a feeling that is comparable to it, even today.

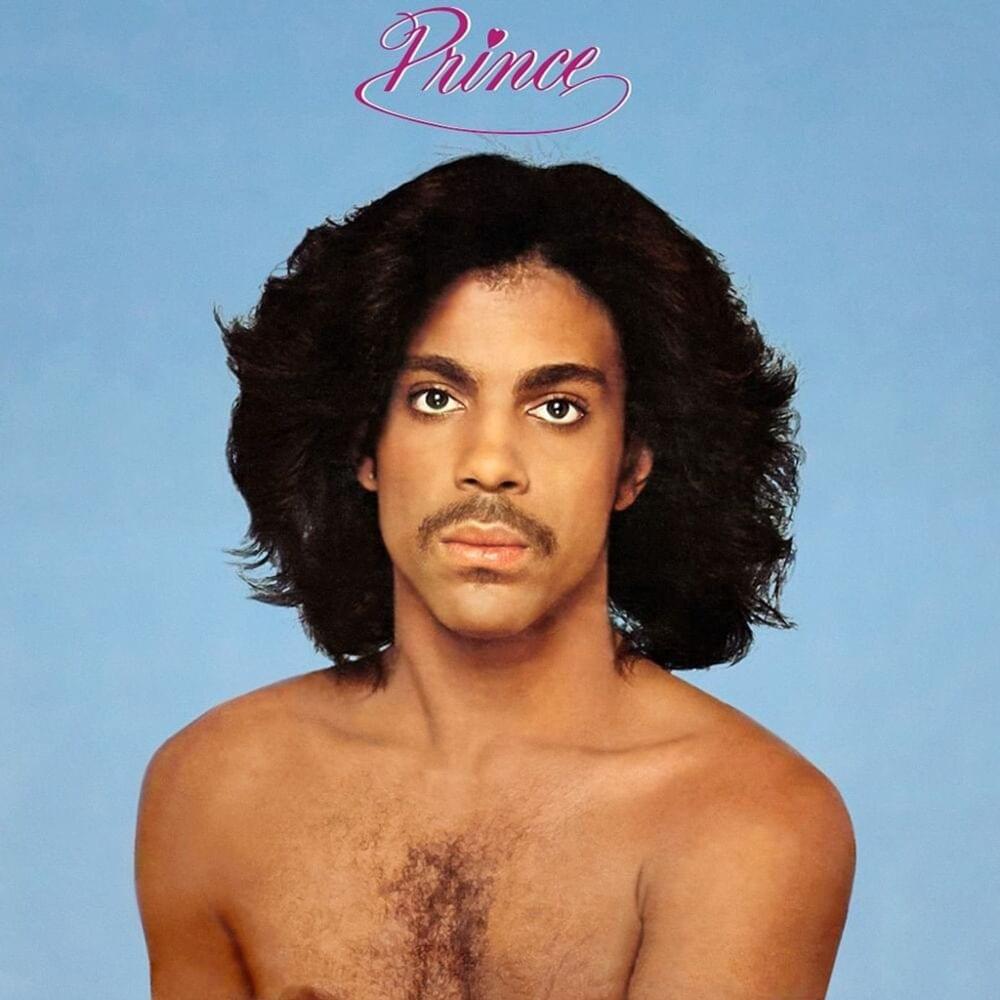

My first visit to see her in California was to her Lankershim Boulevard apartment. The complex seemed fancy and reminded me of a hotel with its balconies and pool in the center of the gated entrance. She hosted me, along with her other two siblings for almost the entire summer. She worked during the day, but she’d leave us stocked with all of the food, snacks, treats and VHS tapes a child could ask for. I must have watched Purple Rain a hundred times while on that vacation. I mimicked every word, and she got quite a laugh watching me imitate the characters and reenact various scenes. I was an animated, dramatic, and humorous child with lots of spice and she would often get a kick out of winding me up, letting me loose, and watching me “go.” Especially if it was bordering on something mildly inappropriate, like quoting Prince’s father saying, “You’re a goddamn sinner!” in a particularly tense scene from The Purple One’s critically acclaimed debut film. She would crack up and I delighted in moving her to laughter. We both understood that we were on the edge of being rascally and we sat in that space together often over the years, especially if it meant we could share a wink and a laugh.

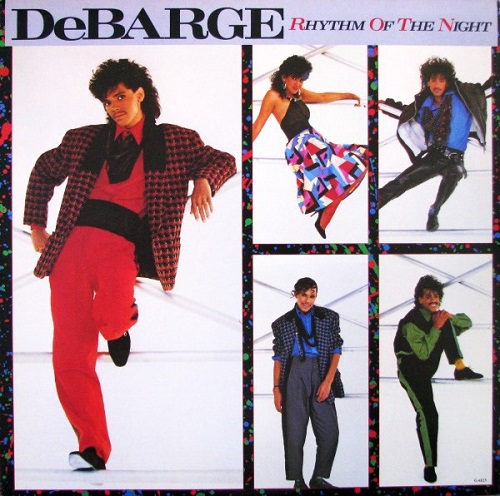

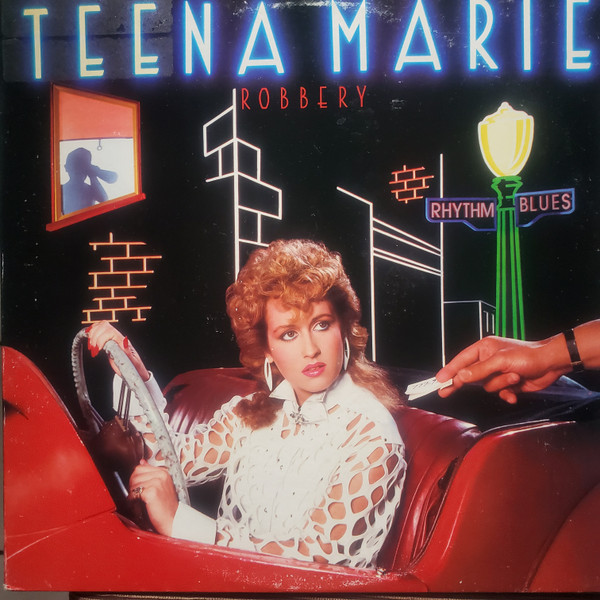

Even though we weren’t living together, as a DJ her musical tastes are what influence me most today. When I was as young as six years old, I was taking stock of her incredible vinyl collection — Sugar Hill Gang, Michael Jackson, Whodini, DeBarge, Teena Marie, The Gap Band, Prince. Being born in the early 1960s made her early 20s the sweet spot when it came to real-time reveling in the now-golden era of R&B, pop, and the emergence of hip hop. I was watching Whodini perform “The Freaks Come Out at Night” on Friday Night Videos. She was partying with the late, great Ecstasy. We all watched Michael Jackson debut his moonwalk on Motown 25, but she’d already seen the future King of Pop perform up close and personal as a member of J5, The Jacksons, and as a solo act.

Levels.

Living in New York City, it’s become the hot thing for DJs to delve into the black lexicon of the ’70s and ’80s at trendy rooftop parties and speakeasies. But I had a sister who lived that music, and that detail made the music hit a little differently for me. For their part, they were simply playing the songs. But for me, each song was a direct line to her. She was there, live and direct. I don’t have enough fingers and toes to tally how many times she’d seen Prince live. Almost all of the Queens. Too many to list. People my age are spinning these classics from some part of the distance. Even if we heard the music coming up, there’s not the experience of seeing these people live at the time of these recordings, or dancing to it in the clubs, or even being in the studio with some of the artists themselves — she had all of that over us. And I took pride in having that connection to her.

I felt like her real-time experiences with the music certified me in a way. When elders would say infamously, “What you know ’bout that?” I would say, “Plenty!” And it was largely because of her. When I would practice my sets, I’d text her a video of a particular blend I was working on. If I was spinning The Jones Girls’s “Nights over Egypt,” I’d make her a quick video dedication. “I know you love this one!” I also loved playing her some of the rarer cuts to see what she had to say about them. Her firsthand anecdotes became invaluable to the way I approached DJing.

Prince, Aretha Franklin, Luther Vandross, The Clark Sisters, Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, and Teena Maria were among her absolute favorites. I’m going to go out on a limb (no pun initially intended) here and say she is The Ultimate Teena Marie Enthusiast. I don’t know of a soul who knows Marie’s music more thoroughly than my sister. I remember when she brought her Irons in the Fire LP to the Grand Concourse apartment I grew up in on one of her visits. I was maybe 6 years old. I will never forget the sounds of “Young Love” and the title track as they wafted through the house. The album, lush with gorgeous orchestral arrangements by the brilliant black arranger Paul Riser, was sonic bliss for me. But that sense of euphoria was present partly because she was the one playing it. Whatever she liked was important to me. Whatever she was drawn to made me listen with a closer ear.

Some years later, on another one of her visits, she and her then-fiancé were driving some of us home from a day of hanging out. She was leaving New York the next day. Her departures were just as eventful as her arrivals. Those eves before she was headed back were always tough for me. This night, it felt like a bag of coal was sitting in the pit of my stomach. I wished I could bottle just a piece of her, so that I wouldn’t have to be without her. The radio was tuned to WBLS and the legendary Vaughn Harper, whose pioneering Quiet Storm-formatted program set many a sentimental mood for 25 years. Teena Marie’s “Casanova Brown” began to play. I thought, Wow, they’re playing this for Marcia. Maybe for us. Since I was young, I never believed in coincidence. There was always some meaning in the seemingly mundane. At almost six minutes, it’s a long song for the radio format, but they played the entire suite-like ballad from start to dramatic finish. I listened intently, grasping the fullness of Marie’s angst as I was suffering my own, although much different in nature. My sister was leaving. And I wished she didn’t have to. It would be like this every time I was with her, either in New York or Los Angeles. I was never ready for her to leave, and I was never ready to come back home.

In the late 90s she took me to see Teena Marie live at an intimate Los Angeles venue. Going out with Marcia for a night on the town was the best excuse to get all dolled up. I dressed in a casual but elegant grey velour tank-and-pants set, my hair in big loose curls made with her electric hot roller set, and my makeup courtesy of the massive level of beauty products on her busy powder room sink. She’d temporarily switched from MAC to Lancôme foundation, and I brushed it all over my face, even though the shade was off. Consequently, my skin looked as grey as my lovely outfit in all of the photographs we took that night. Yikes. But what stands out most to me about that night was sitting across from my sister as she listened to her favorite, Lady T, as she waved her arms high in the air, singing along, smiling, gesturing the lyrics, and having the time of her life.

It was around the time when CDs became the new format of the day that I began buying my own music. There was lots of vinyl in the home and I never felt like I needed to buy it until I became an adult. But with Discmans becoming all the rage in the ’90s and Tower Records being a ten-minute walk from my high school, I began buying the shiny, silver discs in droves. I was a sophomore in high school, and Marcia was coming to New York over the Christmas holiday. I asked her, “Can you bring me some Stevie Wonder CDs?” I was at the height of my Stevie Wonder deep-dive, and I wanted to copy them onto cassettes to make mixtapes. She told me she would, but in my mind, she was going to forget. I hounded her about those CDs for weeks. Each time, she patiently assured me she would bring them, even letting me know the night before that they were officially tucked away in her suitcase. She didn’t forget.

She must have brought about 30 Stevie Wonder CDs with her. I couldn’t believe it! I had asked her to bring “some,” which to me meant she’d bring maybe five or at the most, ten. I think she brought every Stevie Wonder CD she owned. In that moment, watching her unpack stack after stack onto the bed, her beautifully manicured hands clad with gold and shiny stones and long cherry red nails holding as many as she could each time she reached into her suitcase, I realized that she thoroughly understood how important this was to me. And she didn’t want to disappoint.

Despite an almost 16-year age difference, she and I would often spend hours upon hours on the telephone. Being so far away from each other physically, the phone was our lifeline until we could be together physically. It is only now, through the hours of confiding and grieving I’ve done with my best friend on the telephone these past months, that I realize how non-typical that was.

“Think about how many other people must have wanted her time and then think about that level of undivided attention she was giving you,” he marveled as he soothed and enlightened me during a recent phone call. “How many other things she could have been doing with her time, and how she was deliberate in her choice to talk to a 12-year-old instead. Her little sister. How she preferred to. How those conversations and that time together had to have been giving her as much as it was giving you.”

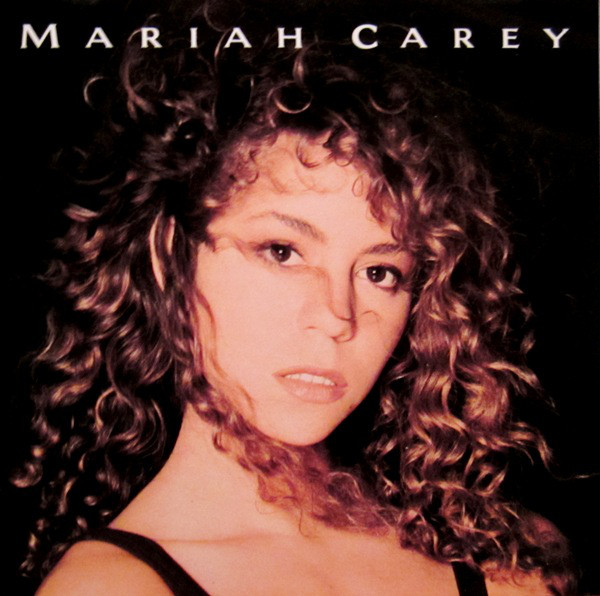

When Mariah Carey’s self-titled debut was released in 1990, I became instantly hooked on the fellow New York native, who was climbing the charts like greased lightening. Her song “Vision of Love” spoke to me, and I practiced it enduringly. Somewhere in our conversation about newcomer Mariah, Marcia asked me to sing it. Painfully shy as I am, it took lots of coercion, but my sister is wildly persuasive. It was almost impossible to tell her no. So I did as I was asked. I sang the first verse of “Vision of Love” to her over the phone. When I finished, I held my breath in the long silence.

“Sing it again! Sing the next part! Keep going!”

By the time I was done, I’d sung the entire song — the bridge, and long stirring ending included.

She was stunned. It was the proudest I’d ever see her of me. She really loved my voice and I have no doubts that her confidence in me and the pure, visceral joy she felt when listening was the precise boost I needed to audition for LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts a year later.

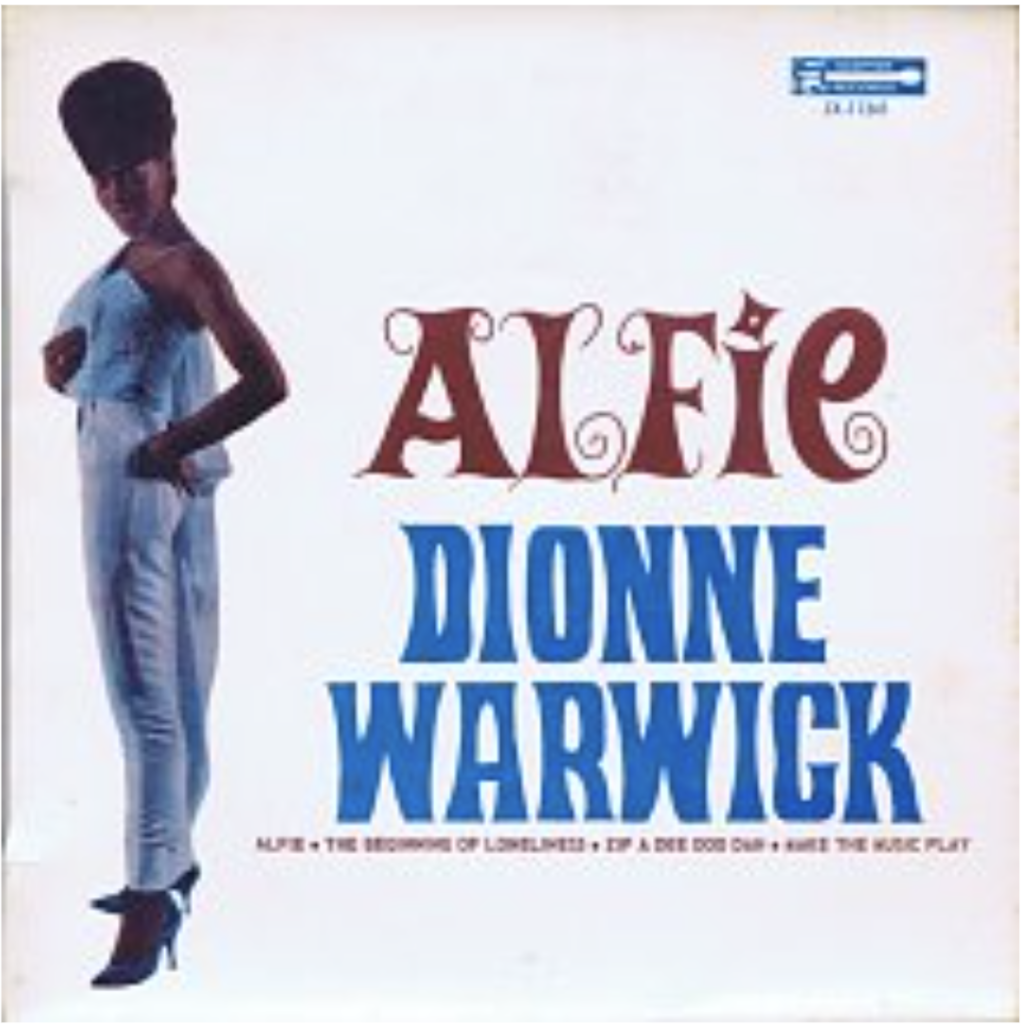

After giving her my best Mariah Carey, she took me under her wing and began teaching me songs for us to sing together. In addition to her sheer passion as a listener, consumer of music, and committed patron of the arts, she was also musically gifted. She had a great ear. She sang in a group for a brief time and had a warm, lovely voice herself. She also had a great sense of harmony. She taught me the Hal David-Burt Bacharach classic, “Alfie,” assigning me the alto part. We’d sing it together on the phone over and over again.

What’s it all about Alfie

Is it just for the moment we live

What’s it all about

When you sort it out, Alfie

Are we meant to take more than we give

Or are we meant to be kind?

And if, if only fools are kind, Alfie

Then I guess it is wise to be cruel

And if life belongs only to the strong, Alfie

What will you lend on an old golden rule?

As sure as I believe there’s a heaven above

Alfie, I know there’s something much more

Something even non-believers can believe in

I believe in love, Alfie

Without true love we just exist, Alfie

Until you find the love you’ve missed

You’re nothing, Alfie

When you walk let your heart lead the way

And you’ll find love any day Alfie… Alfie

I was about 18 years old when I realized that I just may want to be a music writer. At the time, Faith Evans had just released her sophomore album, Keep the Faith. I was a Faith Evans junkie and studied her vehemently. I would read VIBE magazine and daydream that one day one of my essays would land there. I wrote a pretend review, willing my future through my prose, and I asked Marcia if I could bounce it off of her over the phone. I got through the first paragraph — the introduction. She stopped me.

“READ THAT AGAIN?!?”

I will never forget the pride that welled up in me, and I happily obliged, reading it now with more confidence, feeding off of the way it grabbed her. She made me read it a few more times before emphatically stating that I was already a writer. She made me feel like I could have submitted my pretend review that very day. Years later, when I did begin writing professionally, earning awards in the field of journalism, she would become my first editor.

Marcia was a strong writer and an even stronger editor. She happily reviewed my work, being mindful not to ever change the essence of its meaning. She edited with a gentle hand. This said everything about the way she felt about my work, because when it came to business and a time to work, there wasn’t much benignity. She was a tough cookie. She needed to be. When I think about how she climbed the corporate ladder to such heights that she was able to retire by the time she was my age, I understand the diligence, and hard-nosed approach that made her successful in her career. She was a boss in every aspect of her life. So when she took a tender approach to my work, to me, it was because she knew she could. She could because to her, the work was solid. The fact that a woman who had done so much in her own career, saw me as a person blossoming and surefooted in mine, meant so much to me.

“As usual, check me,” she’d always say when returning a piece I’d written that she’d just edited, oftentimes without much notice or time to do so because of strict deadlines I had to adhere to. Never once too busy to do it, either. “Hey Marsh, I gotta turn this piece in tomorrow — you have time to edit it?” She always did. It couldn’t have been convenient every time. But I’d never know it. “Here you go. CHECK MY EDITS CAREFULLY, as I didn’t intend to misconstrue any of your thoughts.” The preservation of my tone, my voice, my meaning was paramount to her. Another time she wrote, “Here’s my first run at it. Check it out. I want to sleep on it and look at it again tomorrow. Let me know what you think.” The honor of her respect was worth more than almost anything. I don’t know if she knew how much it meant to me, until I told her about ten years ago.

In a rare occurrence, it was raining on this particular Los Angeles afternoon, as we sat in the driveway of her home. We had just pulled in from wherever we were coming from when we were having one of our deeper conversations, and it led me to say to her, “What you think of me matters.” I was barely able to get the sentiment out, choking back tears that felt as long as the streams of rain on her windshield. “Oooh, Angelika … what you think of me matters, too.” I don’t think I knew that at the time. But when I reflect … her deference to me as it pertained to my writing, the value she felt as an auntie, the times when she called to ask for my opinion or when my ear was the one she desired to vent to … yes … what I thought of her mattered to her, too. I’m grateful we told each other at least once. I wish we would have told each other many more times.

When I had my son, I experienced an interesting dynamic. Although my sister was substantially older than me, I’d been an aunt to her child much longer than she’d been an aunt to mine. It was trippy watching her navigate this new territory in which I was already quite seasoned for some time. I’d been an aunt since the age of 6, being the youngest of so many siblings.

She was the aunt I expected her to be. Intense, no bullshit, protective, and totally immersed. She responded predictively to almost every video I sent her between our in-person visits. “LOOK AT MY NEPHEW!!!!” He was never so much my son as he was her nephew. As frustrating as it would sometimes be to experience her completely take over the maternal role when it came to my son, I simultaneously understood what was happening for her. She loved him.

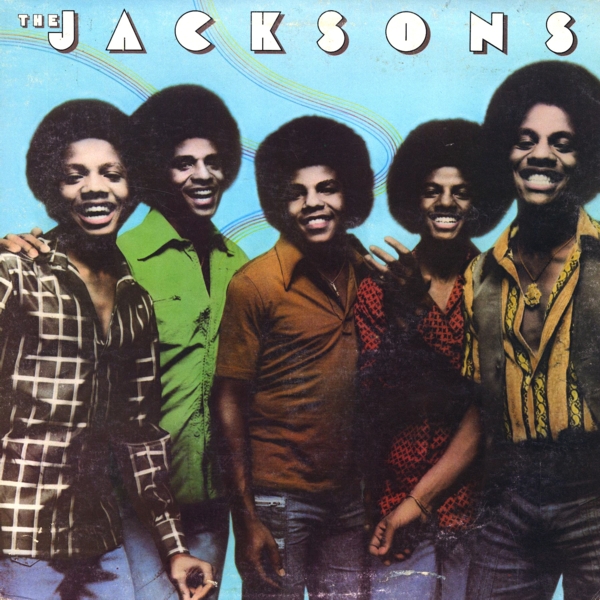

“Do you know the song ‘Blues Away’?” she asked my son when he was at the peak of his Michael Jackson obsession at about 5 years old. He didn’t know it. She was keeping him while I was doing whatever business was at hand. When I got back to her house, she had him immersed in The Jacksons’ 1976 self-titled album, and “Blues Away” became a staple for us — and my phone’s new ringtone to keep us close, as we traveled back to New York.

I’d like to be yours

Tomorrow

So I’m giving you some time

To think it over today

But you can’t take my blues away

No matter what you say, hey

You can’t take my blues away

No matter what you say

What you say, hey, baby

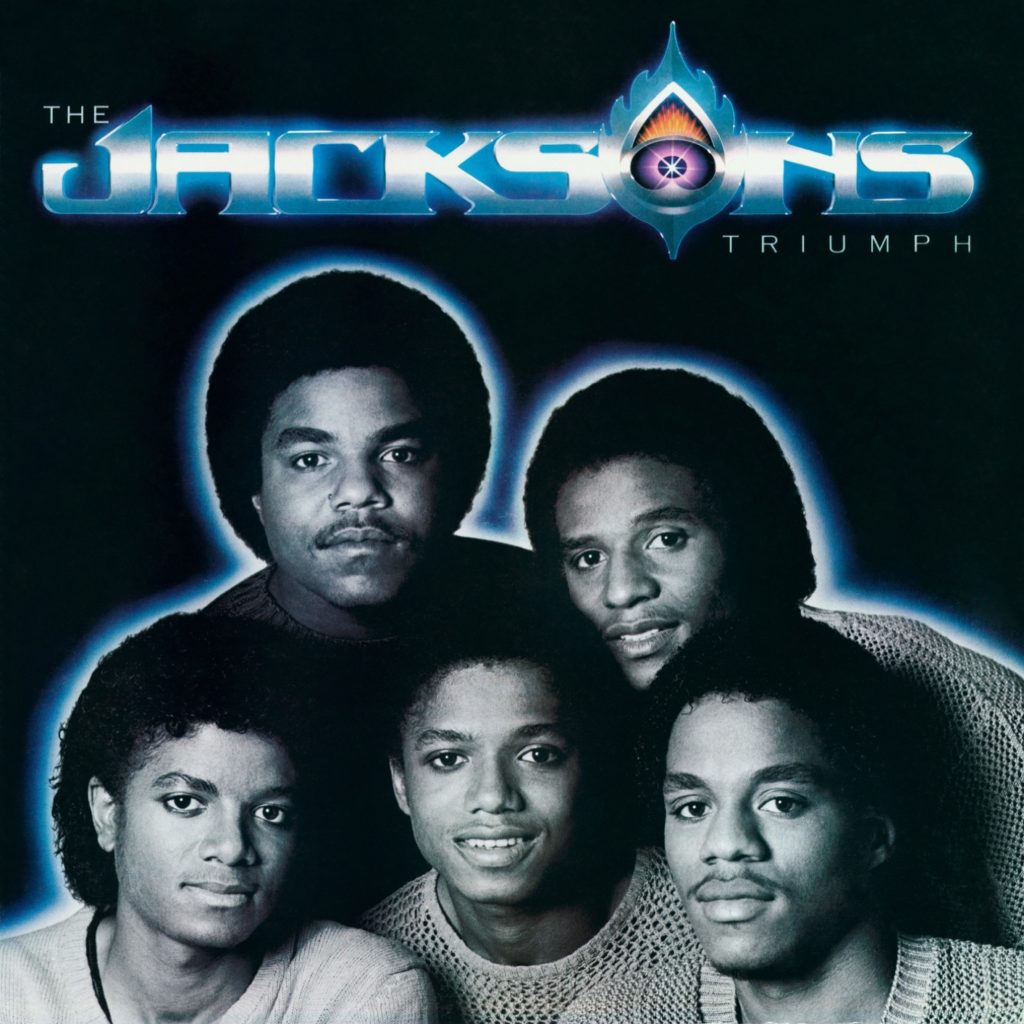

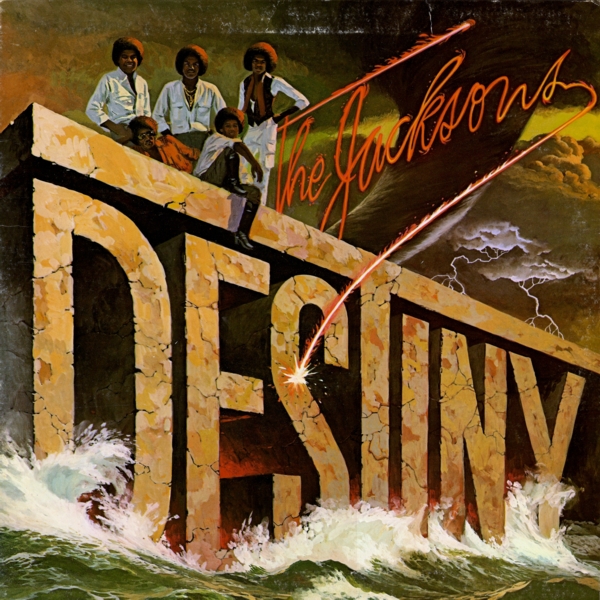

The next song she introduced to her nephew was the delicious dance track “Lovely One” from The Jacksons’ Triumph album, released in 1980. I’d been a fan of this album for some time, but I was a complete fanatic of the group’s Destiny LP, which had been released two years prior. I knew that project inside and out. When Marcia began to dissect Triumph for Riley, I began to spin it almost all the time. The signature horn lines from “Lovely One” were analogous to those of “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground),” and I realized I could blend these two for an ultimate dance experience. A little piece of Marcia, a little piece of me, alchemized for the benefit of the groove. Whatever music she introduced to my son meant as much to me — if not more — as the music she hipped me to. She had the inside track on how to make my presentation of music sparkle just by being herself. She enjoyed making this impact on both of us, and I delighted in her enjoying herself as teacher … as music mentor. I could tell it meant a lot to her. I was honored that she felt proud to be in that position within her nephew’s village.

It’s funny. When you’re a “little sister,” you’re inherently on the receiving end of many things — the good and the not-so-good. Ideally, there is a built-in protection. You’re looked after by default. But I was a fully grown woman with a child of my own and Marcia would still throw her arm across my chest if we were in the car and she had to come to an abrupt stop. She still held my hand tightly if we had to walk through a crowd — her leading the way, pulling me along. She still proudly introduced me to her friends as “my baby sister.” Four decades into this life thing, and I was still her “baby sister.” And the truth is, I loved it. I loved being loved by her. It mattered.

My sister was born on a Monday. And she transitioned on a Monday. For many of the artists who came into their prime as she was blossoming into her own sense of womanhood in the late ’70s, astrology was a heavy theme, and I love the sacred system of the stars. From an astrological perspective, the Moon rules Mondays. The moon and its function in our lives is one of life’s most profound mysteries. My Piscean sister was indeed profoundly mysterious. She was born a mystic. And so, it’s no surprise that in the wake of her passing, she has been so deeply present in my life. While I hold these post-transition experiences sacred, therefore rendering them classified, what I can say is that she is teaching me, in the ways in which only she can, that there is no end. Only transcendence. And ascension.

I would never have fathomed that the questions raised through the lyrics that my sister taught me from “Alfie” could portend so much about sisterhood and our journey through it. Our triumphs and our failures as sisters. Our fervent attempts to reorient ourselves within the bylaws of sisterhood throughout our earthly time together. The vulnerability it takes to be in true sisterhood with another.

What’s it all about?

Time continues to whisper the answers.

What’s it all about Alfie

Is it just for the moment we live

What’s it all about

When you sort it out, Alfie

Are we meant to take more than we give

Or are we meant to be kind?

And if, if only fools are kind, Alfie

Then I guess it is wise to be cruel

And if life belongs only to the strong, Alfie

What will you lend on an old golden rule?

As sure as I believe there’s a heaven above

Alfie, I know there’s something much more

Something even non-believers can believe in

I believe in love, Alfie

Without true love we just exist, Alfie

Until you find the love you’ve missed

You’re nothing, Alfie

When you walk let your heart lead the way

And you’ll find love any day Alfie… Alfie