In Appreciation of Labi Siffre: An abridged reflection on folk music, Black erasure, and an unfamiliar giant.

It’s been 50 years since Black-British singer-songwriter-instrumentalist -poet-activist Labi Siffre released his self titled debut.

In 2017, I began working as a consulting producer on a documentary about musician, playwright, activist, and “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black” composer Weldon Irvine. The general nescience about this important artist was in large measure the genesis of the doc as well as a critical theme in its narrative.

The Unsung Artist is not a new archetype in black music. I have a few in my own family, and I know many people who share that story. During the course of film production, the way I would find myself opening conversations about Weldon was, “He’s an artist that you didn’t know you actually know.” I wanted people to understand that although this name may not be readily identifiable, his essential body of work has created deep cultural connections that have become part of our collective consciousness. I wanted them to realize that learning his name was an opportunity for us to begin to offer a sort of intentional gratitude.

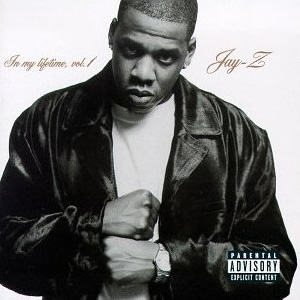

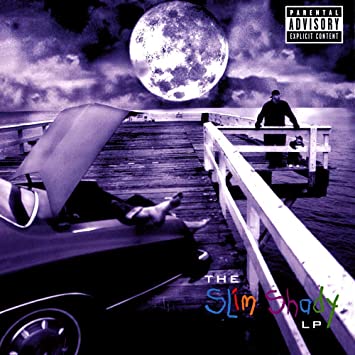

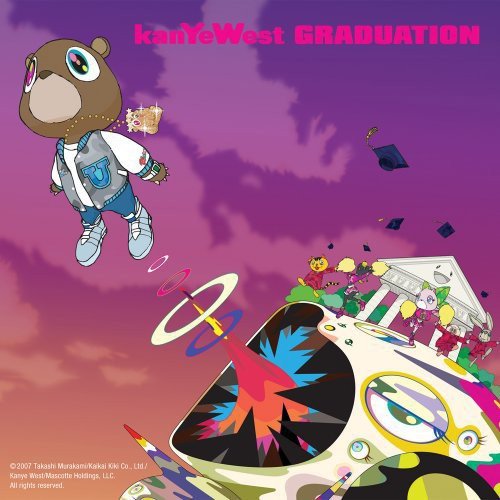

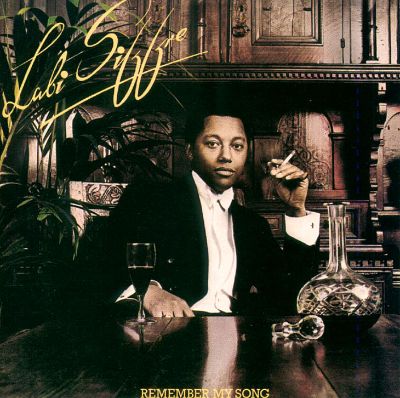

Like Irvine, the music of prolific singer-songwriter and folk-influenced artist Labi Siffre is instantly recognizable, largely owing to sampling. “I Got The…” from his 1975 album, Remember My Song, was sampled by Dr. Dre on Eminem’s debut, The Slim Shady LP, catapulting the rapper to stardom. Before that, Jay-Z and producer Ski Beatz borrowed from the same song on Jay-Z’s In My Lifetime Vol. 1 masterwork, which spent a whopping 70 weeks on the Billboard charts. Later, Kanye West would sample Siffre’s “My Song” (Crying, Laughing, Loving, Lying, 1972) on his 2007 album, Graduation. In 2014, singer Kelis beautifully covered Siffre’s “Bless the Telephone” (The Singer and the Song, 1971). More recently, music supervisors would find a gold mine in Siffre’s affectional “Watch Me” from the same album, as it was featured in the first season of the hit NBC drama series, This Is Us. Yet, for all of Siffre’s musical seepage into American popular culture, his name remains widely unknown to the masses of us.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Labi Siffre’s self-titled debut. Siffre, a Black man from Hammersmith, London, came on the recording scene in 1970, after spending time in the house band of Annie’s Room, a jazz nightclub owned by Annie Ross of the famed jazz vocal group, Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. Citing Monk, Miles, Mingus, Coltrane, Billie, and Sassy as his songwriting influences along with Little Richard and Muddy Waters, Siffre found his earliest musical inspirations by way of his brother’s extensive record collection. Siffre released ten albums over the course of the next three decades, with a particularly creative streak in the 1970s, as a predominately folk-oriented musician.

Openly gay, black, and atheist, it is relatively safe to deduce that Siffre’s trajectory toward eminence was impeded in a society where white supremacy and religious provincialism were and continue to be pervasive influences. Perhaps it is also presumptuous to surmise that fame or celebrity were in any way a goal of the visionary singer-songwriter. However personal the gripe may be on the matter of Siffre’s relative obscurity (his intervals of reclusiveness duly noted), the sobering limitations for black recording artists is a veritable reality. Namely, within folk music.

Like most of America’s earliest auditory art, its history is unfailingly looted by deniers armed with unmerited access to powerful platforms that allow them to perpetuate false and damaging narratives. To date, Folk’s prevailing image is well-meaning, white people with long hair strumming guitar strings and singing about peace and love. The problem with this composite is that it woefully crops out its origin and craftspeople. Apropos of mention, let it also be said that Black people are all-too-often relegated to the “architect” epithet. While it is true that Black people are the founders of most traditional American music, folk included, these truths are, as a matter of practice, deported to the back burner of relevance or importance. The distortions of black value overall are essential to the lies that shape the story of American music, as told to us.

As a means to an end, the creating of an art form has to somehow therefore pale in comparison to those who partake in and profit from its adaptation, its interpretation, its theft. Hence, it inspires me to make it plain that Black people are not only the architects of American folk music, but were quintessential participants in its expression, inspiring all those who would partake and subsequently become the faces of the tradition. Like all black American music, there is an inextricable link between freedom of expression and the creativity birthed from the quest. You don’t have American music without an expression of resistance. You don’t have a need for resistance without the presence of oppression. In America, you don’t have oppression without the presence of White supremacy. Folk music is black music. And while there is most certainly a beautiful and vast and rich contribution to the genre from white musicians, out of its proper context, this contribution becomes grandiloquent by way of an irresponsible, reckless, and harmful narrative that not enough white artists bother to correct. To deny the genesis of the folk genre and its participants and to willingly participate in the erasure of blackness from the folk tradition is absurd and unacceptable.

The list of indispensable, founding folk artists whose tradition has made the folk genre possible is rich and extensive. Artists like Leadbelly, Elizabeth Cotten, and later, Odetta, are but a few of the biggest influences of most white folk musicians who would come to prominence in the folk genre’s golden era of the ’60s and ’70s, and the more forthcoming of them — greats like Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and Pete Seeger — would proudly tell you so. (Dylan would also just as proudly admit to lifting from his good friend Len Chandler, another unsung, Black folk artist, at the beginning of his career.1)

While I’d been fostered by folk-soul/folk-rock greats like Bill Withers and Richie Havens, it wasn’t until I heard Tracy Chapman as a young girl that I actually saw a black woman rise to prominence as a folk-leaning artist in real time. The musical daughter of artists like Cotten, Odetta, and Sweet Honey in the Rock, but also someone who grew up in the 1970s, influenced by soul, jazz, country, and blues, Chapman was one of a few black folk-identified artists I heard in the 1980s, and she was for sure the only black, woman, folk megastar I saw. I remember a distressingly misguided notion floating about that Chapman was “doing white music” and this disconnect remains, although artists like Meshell Ndegeocello, Ben Harper, Brittany Howard, Toshi Reagon, and even India.Arie, Lauryn Hill, and H.E.R. have tremendously closed the gap. But whatever erroneous claims were being flung about with regard to Chapman and her blackness or her music’s perceived whiteness, my inclinations toward folk music were always strong. The sound purely appealed to me.

“The insistence that one should be ‘ethnic’ is endemic, irritating, and insulting,” Siffre reflected in a 2012 interview. The UK’s music industry is historically analogous to that of the States when it comes to Black artists who desire to color outside of the industry’s imposed delineations. The boxing-in of Black artists into agreeable categories creates deliberate distance between themselves and their own architecture. Almost always, the result is a perpetual frustration accompanied by the haunting backdrop of marginal success for artists who — but for their blackness — would have otherwise gained mass appeal, if not critical acclaim. Labi Siffre and someone like Nick Drake, for example, should be discoursed with similar deference. Instead, Siffre, unlike Drake, is largely ancillary when it comes to the wider discussion of ’60s and ’70s folk. By no means should he be.

“I’m in favor of accepting the fact that when one is writing, one is always writing about oneself, no matter how you express yourself on whatever issue,” Siffre said in a 1997 interview with U.K. magazine The Argotist.

The notion that all writing is essentially autobiographical is a principle motif in Siffre’s oeuvre. From his Twitter bio — Atheist, Homosexual, Black, Songwriter, Musician, Singer, Poet, Social-Commentator. Twice a widower. English, British, Philosophically/Spiritually an EU Citizen — one gleans that his music examines nearly each description contained in the 160-character allotment. An artist historically committed to challenging the norms of society’s immoralities, through his music, Labi Siffre has consistently leaned into himself, his experiences, and the identities that he affirms for himself with a striking degree of honesty, vulnerability, and bravery.

An admitted “poet first,” Siffre’s lyricism is visceral and deeply intimate. Among a series of torch songs, his debut album also tackles generational tensions concerning the social dynamics of the 1960s, with an ever-increasing focus on conscious themes throughout his recording career. Societal ills like racism, homophobia, and war were the roots of Siffre’s blistering lyrical content. Amplified by his astounding vocal clarity, his lyrics refuse inconspicuousness. They also never compete against his remarkable musicality.

Each song has a way of beautifully blindsiding you with no real predictability of approach. He has a way of surprising the listener by turning a progression on its head, taking it in a totally unexpected — and always enchanting — direction. He masterfully folds irony and humor into his music through a rhythm, a lyrical sentiment, a run on his guitar, or by using brilliant paradoxical concepts. There is something daring, fresh, and unabashed about Siffre that makes his music practically addictive.

There’s also the influence of Siffre’s virtuosity that I find quite apparent, by way of his inclinations for using intricate time signatures, string arrangements, and unpredictable harmonic progressions. On a song like “Here We Are,” for example, Siffre’s dreamy vamp-out is reminiscent of the extraordinary Argentinian-Swedish singer-songwriter-guitarist, José González. His enchanting “Blue Lady,” is another example of a song that feels like a blueprint for contemporary folk artists like González with its mixture of African percussive elements and multitudinous harmonic nuances.

“The insistence that one should be ‘ethnic’ is endemic, irritating and insulting.”

— Labi Siffre

By 1975, Siffre had begun pushing past the margins of what was considered to be in the folk genre, with his first three albums solidifying his eclectic and ingenious expressions and interpretations. Labi Siffre, The Singer and the Song, Crying, Laughing, Loving, Lying, and For the Children each fully captivating and in good company with the early ’70s prolificacy of artists like Stevie Wonder, Donny Hathaway, Joni Mitchell, and Earth, Wind & Fire. But Remember My Song was a clear creative departure from previous works. “I Got The…” opens with a now-classic guitar lick. Chock full of funk, via the drums of rock drummer Ian Wallace (Bob Dylan, Esther Phillips, Bonnie Raitt), guitar-bass duo Chas Hodges and Dave Peacock, and Siffre himself on keyboards, Siffre makes a statement from the first track that the breadth of his artistry was that much more massive. The song offers not one but two stunning passages that helped define the advancement of hip-hop.

Siffre’s appeal to hip-hop producers is poetic considering that on “Too Late,” the first track from his first album in 1970, he delivers scathing, diss-track level lyrics, constituting one of the greatest “Get lost!” songs of his time. Yet, for Siffre, much of the engrained machismo of hip-hop is in direct conflict with the core of his personhood. On the matter of granting Dr. Dre permissions to use “I Got The…” for Eminem’s “My Name Is” he said, “Dissing the victims of bigotry — women as bitches, homosexuals as faggots — is lazy writing. Diss the bigots not their victims. I denied sample rights till that lazy writing was removed. I should have stipulated ‘all versions’ but at that time, knew little about rap’s ‘clean’ and ‘explicit’ modes, so they managed to get the lazy lyric on versions other than the single and first album.”

In May of this year, Siffre released “(Love Is Love Is Love) Why Isn’t Love Enough?” a song directly advocating gay rights. In 2020, this may not be considered a gallant act, but considering that Siffre’s open homosexuality dates back to at least the beginning of his recording career, the song symbolizes both Siffre’s commitment to fusing his art with his activism, and the road his contributions continue to pave along the same path that Bessie Smith, Ma Rainy, Tony Jackson, Billy Strayhorn, and others cobbled. His 1987 hit single, “Something Inside So Strong,” which brought him out of his retirement of some measure, was written as part of the growing, global condemnation of apartheid in South Africa, becoming his most successful song, to date. Yet, Siffre also discloses the more personal roots of the song years later. “As soon as I’d written the first two lines — ‘the higher you build your barriers the taller I become’ — I realized with a shock that I was writing about my life as a homosexual.” Siffre, who officially registered a Civil Partnership with his partner of fifty years in 2005 (the soonest this was allowed in the UK) that lasted until his beloved’s passing, continues to write and publish poetry, and engage in social activism for LGBTQ rights.

The effects of Siffre’s unconcealed queerness on his career arc may be as indeterminable as the effects of his devout atheism, but such ostracized identities — especially encased in blackness — certainly allude to an arduous path. “With neither my permission nor my understanding, I was baptized and confirmed a Catholic,” says Siffre in an interview with the U.K. quarterly, New Humanist. Siffre recorded several songs speaking to his absence of belief in God, most notably on his 1973 album, For the Children. On the song “Prayer,” Siffre plays a lullaby-like melody while sweetly singing of an at-best apathetic Creator, considering the pain and anguish experienced on Earth by the grieving women described in his lyrics. The song ends:

So God in heaven above / What are you thinking of?

Is this the way you play?

Well, can’t you hear them weep? / Now children, mind your feet

Maybe God has gone to sleep

Siffre follows up with “Let’s Pretend,” a call for a leveling up of humanity. I would describe this song using spiritual nomenclature; it is a call to connect to one’s higher self. As someone who is not at all religious, but is a devoted believer in a Divine Creator, I find it difficult to find offense in Siffre’s expressions of non-belief within the context of his lyrics. The song calls upon those who use religion as a means to an end, to instead live up to the actual tenets of scripture:

Let’s pretend we believe his holy word

He has spoken and we have heard, let’s pretend

Let’s pretend ‘though he spoke through different men

The basic truths remain, let’s pretend

Let’s pretend that the numbers five to ten

Were written for all men (with lightning as the pen)

Let’s pretend, let’s pretend what happened then

Let’s pretend

Let’s pretend that the Pope sells all his jewels

To feed the hungry, ooh let’s pretend

Let’s pretend religious leaders say war is wrong

No matter who is strong, let’s pretend

Let’s pretend religion excommunicates those

Who deal in hate and leaves them to their fate

Let’s pretend these evil people give a damn

And start loving their fellow man

Let’s pretend

Over forty years later, I find connection between this song and the words spoken by Siffre at the close of his 2017 TEDx Talk, entitled Disturbing Definitions. “We don’t find meaning, we make meaning, and then we lack the courage to accept responsibility for the meanings we make. If meaning is just laying around, and we find it, we are not responsible for it; we’ve just come across it in untidy heaps, scattered across a panorama. If we make meaning, that makes us responsible for the meanings we make, and that responsibility takes us out of our comfort zone.”

The righteousness in Siffre’s work is his sheer unwillingness to mince words or equivocate, whatever the subject matter. Nevertheless, an artistry wholly devoted to truth is inherently incongruous with the codes of the music industry at large. To be an unwavering force in an industry which values only the veneer of virtue, Siffre’s messages become that much more significant because for artists like him, the price paid to be free affords the demanding our homage.

In honor of the 50th anniversary of Siffre’s debut release, it’s my hope that you’ll explore the catalogue of Labi Siffre. For the purposes of this piece, I’ve concentrated on what would be considered the creative pinnacle of his opus, but I encourage you to become familiar with the entirety of the bold and vastly creative songwriter and singer whose name should at long last be attached to his masterpieces.

1. Denise Sullivan, Keep on Pushing: Black Power Music from Blues to Hip-hop (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2011), 20.